We love EmptyEpsilon. We have been using it since early in our games, back in 2016. We have invested heavily in learning and using it over the years.

First Contact

Initially, we extended EmptyEpsilon to our needs by configuring and communicating with the server HTTP API: we wrote a javascript driver that takes care of communication, a server management CLI to help managing it, an OSC gateway and an engineering extension that replaces the repair system with custom hardware panels spread across the ship. Later, we’ve made some contributions to the EmptyEpsilon project itself by adding documentation.

However, we avoided getting into the code of EmptyEpsilon itself, as it appeared complex and cumbersome. The fact that it was written in an old version of C++ did not help.

The Chasm

After our first few games with EmptyEpsilon, however, we’ve learned that some features in the game itself have to change. At the top of our wishlist was handling extremely large maps gracefully. Our games had maps that were huge compared to what EmptyEpsilon was designed to handle. It became evident that we’re stretching the limits of the user experience: Sectors that are far away from the center of the map got ridicules names, and both GM and Relay officers had to tediously scroll the map over and over again to switch between locations. This affected our ability to deliver the game. It was a big deal for us.

So we dove into the C++ and somehow managed to write features that addressed these issues, and asked to have them merged into the EmptyEpsilon project so we can use them in our games. And after 9 months of reviews and rewrites, all of our feature suggestions were rejected, even if not in so many words. It seems that EmptyEpsilon was designed for short game sessions, and a lengthy LARP was not a significant enough use-case to justify the added complexity.

During that time we noticed there were some independent variants of EmptyEpsilon out there in the open-source scene. We specifically noticed one lead by tdelc who had many helpful features and screens that were also rejected by the original project. Some of his features also happened to be on our wishlist. We should have guessed he was a LARP organizer as well.

So we said “Fork it”.

The Fork

In software engineering, a project fork happens when developers take a copy of source code from one software package and start independent development on it, creating a distinct and separate piece of software. –Wikipedia

We knew that it was going to be hard to maintain a fork. It takes considerable effort to continue developing a fork, all the while addressing the changes in the original project. The more changes one makes in a fork, the harder it is to maintain it.

We naturally started by adding the much-needed support of large maps, and then went on to copy many features from tdelc. It was a very productive week for us.

But then we had to address some auxiliary issues, like figuring out how to build a working game application and a good development cycle. So we built some release tools, and later published a popular developer guide to help other developers set up their environment. All the while we kept offering bug fixes and updates to the original project.

The big features rush

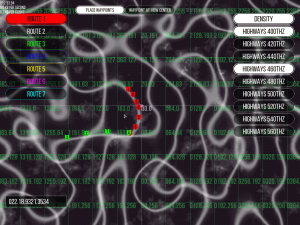

At some point, we looked back at our wishlist and decided to take on a more significant change in the game: adding a navigation system. We’ve invented a mechanic based on invisible “space highways” loosely inspired by marine currents. And to all our amazement it worked. We’ve managed to add a new station to the ship (the Navigator) that perfectly fit our LARP’s needs. It began to feel like we were getting the hang of it, C++ with all its clunky tools seemed less scary, even if the development time and effort were still high.

At some point, we looked back at our wishlist and decided to take on a more significant change in the game: adding a navigation system. We’ve invented a mechanic based on invisible “space highways” loosely inspired by marine currents. And to all our amazement it worked. We’ve managed to add a new station to the ship (the Navigator) that perfectly fit our LARP’s needs. It began to feel like we were getting the hang of it, C++ with all its clunky tools seemed less scary, even if the development time and effort were still high.

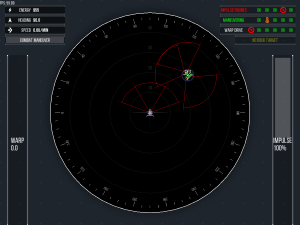

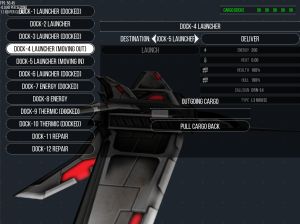

After that, it was hard to stop: the next feature was making the ship a drone carrier, with a station for maintaining and launching drones from within the ship, and many drone pilot stations to operate the drones. We’ve added a tractor beam capability so that the ship can retrieve “dead” drones for repairs and such. This expanded our game’s capacity and provided interesting connections between stations that did not exist before. The tractor beam proved to be the most fun and versatile tool in the ship, allowing creative solutions to otherwise dire situations.

After that, it was hard to stop: the next feature was making the ship a drone carrier, with a station for maintaining and launching drones from within the ship, and many drone pilot stations to operate the drones. We’ve added a tractor beam capability so that the ship can retrieve “dead” drones for repairs and such. This expanded our game’s capacity and provided interesting connections between stations that did not exist before. The tractor beam proved to be the most fun and versatile tool in the ship, allowing creative solutions to otherwise dire situations.

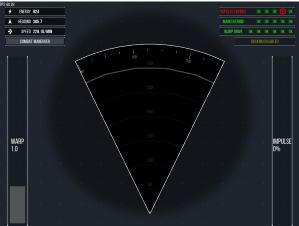

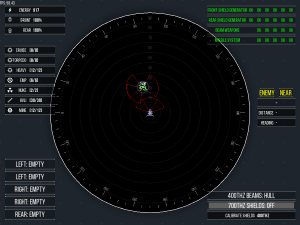

Then we began addressing the screens themselves: EmptyEpsilon was designed primarily for touch screens, and we preferred joysticks and keyboards, so having the user interface “clickable” became a burden both on the code and on the user experience. We wanted more actionable information on-screen, with less interactive elements (inspired by Bret Victor’s article). We began replacing station screens one by one, rewriting them from scratch according to new design principles, and making them simpler than the original.

Then we began addressing the screens themselves: EmptyEpsilon was designed primarily for touch screens, and we preferred joysticks and keyboards, so having the user interface “clickable” became a burden both on the code and on the user experience. We wanted more actionable information on-screen, with less interactive elements (inspired by Bret Victor’s article). We began replacing station screens one by one, rewriting them from scratch according to new design principles, and making them simpler than the original.

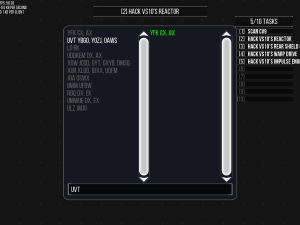

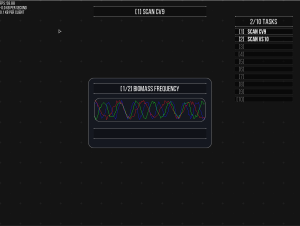

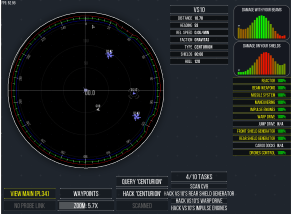

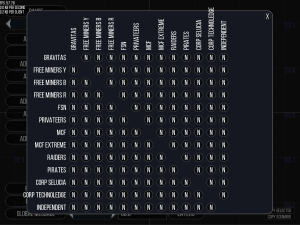

Then we removed some mechanics that we never needed in the first place, like the reputation system, and added more complex features like connecting multiple GM stations, tweaking factions diplomatic alignments, sending scan and hack tasks to new stations, manually control of AI ships from the GM station on demand, communicating with the ship’s computer, password-protecting database entries, and so on.

Then we removed some mechanics that we never needed in the first place, like the reputation system, and added more complex features like connecting multiple GM stations, tweaking factions diplomatic alignments, sending scan and hack tasks to new stations, manually control of AI ships from the GM station on demand, communicating with the ship’s computer, password-protecting database entries, and so on.

The drift

We made efforts of suggesting most of what we did to the original project. The utilities and fixes got accepted, while changes of behavior got rejected.

As a result, other game organizers that track the activities in the EmptyEpsilon project approached us, asking for help with features for their own games: we helped Outbound hope customize their game, and offered a hand to Kilted-Klingon in his events, and coordinated with tdelc on features and bug hunting.

We were making so many changes to our fork, in so many places, that at some point the overhead of trying to keep up with the original project was not worth the effort anymore. We stopped trying to keep up, and the gap between the forks became un-bridgeable.

The aftermath

EmptyEpsilon is a great game. It offers a great versatile experience out of the box, while being open for extensions and modifications in multiple ways. We’ve used it extensively, learned a lot from daid’s work and designs (some lessons learned as well), got a lot of value from it ant gave a lot back to the community.

But as much as we’ve enjoyed this crazy ride, EmptyEpsilon never really gave us the freedom we need to make games the way we envisioned them, due to its inherent limitations. We’ve outgrown it, time to move on. We are starting a simulator of our own, from scratch, that will fit our vision. It will take years to complete, and in the meanwhile, we will continue using our EmptyEpsilon fork.